At the roots of Sake: the rice

- Benoit Roumet

- 16 juil. 2020

- 4 min de lecture

Dernière mise à jour : 9 sept. 2020

You have certainly read that sake is produced in Japan of course, but also in the USA, in other countries and even ... in France as « Les Larmes du Levant » in Pelussin and Wakaze in Paris region. We will speak about these producers later in this blog.

But today, let's focus on nihon shu (Japanese sake) because Nihon shu is only sake produced in Japan with japanese rice grown on the archipelago.

Some geographic reminders on Japan

Japan is an archipelago with a lot of islands (almost 7,000), located in the northern hemisphere between the 20th and 46th parallels.

4 main islands form Japan, Hokkaido in the North, Honshu where the mega-city Tokyo is located, Shikoku and Kyushu. As you can see on the map, northern Japan is at the same level as the city of Lyon while Tokyo is on the parallel of Malta. If you add to that you are on an island with a lot of mountains make you understand that the country knows a multitude of sometimes harsh climates, and except Hokkaïdo, with a climate really close from Europe, Japan knows quite strong episodes like typhoons, rainy season and other excesses of nature.

In an administrative point of view, you can find 45 prefectures (the equivalent of french regions) in Japan. These prefectures will be the geographic unit I would use most often in this blog.

The best of rice

As we saw in one of the first posts, rice is of course the best known ingredient for making sake. Rice is also one of the bases of Japanese food but to get our fermented drink, you need to use specific varieties of rice, rice for sake or sake maï.

The rice used to produce sake goes through many and sometimes complex steps before entering the process of making sake.

The first, which we will come back to in more detail, is polishing.

In fact, when you use rice for cooking, it’s already polished, a part of the outer shell has been removed (generally 92% of the starting grain remains). For sake, we usually start from 70% (30% of grain removed) and we can go down to 35 or even 30% (which is quite rare).

The closer you go to the heart of the rice, shinpaku, the higher the starch level is. This polishing will influence the flavors and aromas you will find in the sake.

Great classics with regional rarities.

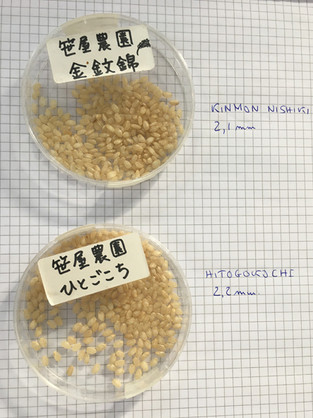

There are 104 varieties of sake rice grown in 45 prefectures in Japan. The first 5 varieties represent over 70% of production (2014 figures).

The rice used to produce sake comes from crossbreedings and selections made year after year in the agricultural research centers of the various Japanese prefectures.

Yamada Nishiki: it was created in 1923 and finallly named in 1936 in the Prefecture of Hyogo (where the second edition of Sake Selections is held in 2021). He is the "king" of sake rice. Resistant to strong polishing, it also has all the qualities to make full body and fragrant sakes. It’s one of favorite rices of the Toji ("sake master") which explains its first place in the hierarchy of sake maï, 33% of the sake rice production in 33 different prefectures even if Hyogo concentrates 70% of the production of this variety.

Gohyakumangoku: created in 1938 in the prefecture of Niigata but baptized in 1957 (because of World War II) it was developed for the colder regions. Its ability to remain firm outside and tender inside after steaming makes it particularly interesting to produce koji (we will back on koji in a future post).

Miyama Nishiki: a little more technical, this rice was created in the 1970s near Nagano thanks to the effects of gamma rays on Takane Nishiki. A nice grain and a very interesting shinpaku made it the third most produced variety in Japan.

Omachi: rice of later maturity, it is the oldest rice cultivated for sake in Japan. Its history started in 1859. First used as table rice, it was adopted by the sakagura ("sake cellars") because of the size of its grain and its shinpaku (the heart of rice - see drawing more high). Its production dramatically felt during the Second World War and never came back to its historical levels. Today, professionals from Hyogo Province and Okayama are relaunching production thanks to the umami developed in sakes made from this variety.

Dewasansan: it’s the 5th on the list but even more than the first 4, Dewasansan is very connected to the Yamagata region where it was created in 1985. It allows the production of a very specific sake, specificity reinforced by the use of Yamagata yeasts and a local Koji-kin. Yamagata sakes is also a geographic indication since 2015.

Back to basics

We know, since few years, the promotion of less known varieties of rice, neglected in the past because they are less easy to cultivate or more fragile and difficult to use in the creation of sake.

A trend coming from the will to differentiate in a strong competition, certainly, but if you listen to the speeches of the sakagura owners, you can feel a strong need to return to important fundamentals, a strong desire to re-root the sakes in their region of origin.

One of the finest examples is the Daishinshyu sakagura in Nagano which, in a global thinking, works in partnership with local rice farmers. Development of organic cultivation, permanent exchanges, everything is done to bring rice to perfect maturity in order to produce unique sakes impossible to make anyhere else.

This strong trend, sometimes accompanied by a return to old methods, is to be compared with modernism and the desire to give sakée moderne style to reach new generations. These two evolutions respond to each other but they are not opposite, just showing all the richness of the world of sake.

Commentaires